Most of us are familiar with the idea of a standard upward sloping learning curve. As time progresses, growth increases toward a relative plateau. As parents, in height, weight, math, reading, or anything else that can be tracked, we assume that at any given point in time, we’ll find our child further along that curve than the last time we checked. Whether the assumption is reasonable or not, finding anything other than progress could be cause for concern. This is one of the reasons it is so important for parents to understand that Montessori education is non-linear.

The instinct to track your child’s growth begins the moment you learn you’re about to be a parent. In-utero, we measure growth in millimeters and the practice basically never stops. I can vividly recall the attention to detail with which I recorded my son’s bowel movements during his first days of life. It was a thoroughness I had rarely applied to anything in my own life up to that point. Of course, by my fourth son, those early diaper changes were more like a NASCAR pit crew experience, minus the precision. Overwith and forgotten in about 10 seconds.

Although he was 100% healthy, in those early weeks with my first child, I had a lurking feeling that in the absence of my diligent record-keeping his development could somehow veer off course. I also expected that if I kept track long enough, I’d be able to look back and see the progress of my fathering efforts. Although, I admit I was never fully certain how bowel movement color change indicated progress. Either way, without close attention, I knew I would miss some of those moments of growth. It is the parent version of “FOMO” (Fear of Missing Out). That not-knowing was almost as worrisome as actual regression itself. Admittedly, it was a brief stage in my parenting life, but a time I will never forget. 20 years later, all of my boys have followed widely different and sometimes inconsistent paths with plenty of peaks and valleys. With very few exceptions, they all continue to grow and develop in the right direction whether I check on them or not.

Back in my new-dad years, doctors and educators told me more than once that each child develops on his own timeline and I should try to remain flexible in my expectations. I also understood this fact quite clearly through my Montessori training. One benefit of working with so many educators, parents and children is that I’ve seen first-hand how human growth is virtually unavoidable. I’ve also seen that it is very inconsistent when looked at over time. Without that experience and all the experts I’ve known, I’d probably still be checking in on my child at every opportunity. So I know it may be a fool’s errand to suggest that parents (especially new parents) just take my word for it, leave things alone and simply trust that everything will work out. We can tell ourselves this and maybe half-way believe it, but without a concerted effort we cannot escape the creeping knowledge that the curve is always there. Always shortening as time ticks away.

Unfortunately, in our efforts to understand our world, human nature often leads us to oversimplify the data. That’s why there are so many Youtube videos, which seek to explain incredibly difficult concepts of science in the simplest of terms (and images). It’s just easier if someone else digests it for us. These videos are fantastic, but every time I watch them I can’t help but remind myself that there is no way I can fully grasp what the person who created this video knows. In the same way, the growth of a child’s mind and body are simply far too complex for anyone to understand without years and years of training, research and experience. Yet at the same time, understanding your child is a parent’s primary responsibility. That’s one of the reasons why long ago, the educational progress was reduced down to letter grades. It doesn’t get much more black and white than an F.

The standard learning curve with grades and test scores creates a nice and tidy set of conditions; left=bad, right=good. Low=failing, high=achievement. It allows parents and teachers to check in anytime they want in the hopes of finding a pre-digested, simplified explanation of what they expect to see. While this method of assessment works fine when a child’s learning is uniformly improving, unfortunately, it rarely helps parents to feel confident enough to act in the face of the unexpected.

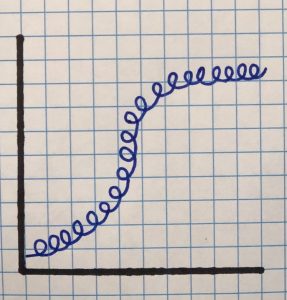

In our classrooms, Montessori teachers consider the child’s growth along that same standard curve. However, rather than consider it year-by-year, our learning curve extends out over the entire three-year cycle. In the primary classroom, this cluminates in the Kindergarten year and is often where the majority of a child’s growth will occur. However, instead of being one smoothe arching line, it is actually thousands of connected spirals in a row. Picture a giant slinky stretched out toward infinity. As the child moves along these spirals, which sometimes double back on themselves, periodic check-ins might indicate a point anywhere on the entire spectrum from progress to stagnation or regression, but appearances may be deceiving.

This is because when we introduce children to new concepts in the Montessori classroom, they apply them in a way that matches their individual abilities, needs and brain development as well as their unique interests in the moment. From there, we stay with the lessons as long as we can. Through repetition of work, the child begins the approach toward mastery. In a traditional linear educational model, this momentary acknowledgement of “success” might be the time to “level-up” and move onto the next skill or standard, sometimes regardless of what the child wants or needs. However, our primary concern is that these new ideas become internalized and take root for future use.

As we see evidence of understanding, a Montessori teacher may use this moment to introduce a similar exercise, a parallel skill or an extension of the base concept. Oftentimes, doing so requires the child to use the concept they have learned in a different way. Sometimes children must even disassemble what they have learned to re-examine the parts, reconstruct them differently and re-learn them all over. Suddenly the child may seem to have difficulty with a concept he or she once appeared to understand. A superficial check-in during this process would almost certainly give the impression that the child is struggling or even “behind,” when compared with peers. However, rather than being cause for concern, struggle is exactly what we want because it is evidence of effort and growth.

Dr. Montessori recognized the stark difference between the myth of linear learning and actual child development in creating her planes of development. In this model, children develop through each 6-year plane with an obvious ascent and decline from beginning to end. At the end of each plane or the beginning of the next, the child “appears as a re-created being” (“Montessori Today” — Paula Polk Lillard pp. 7) sometimes nearly unrecognizable from the child of the previous plane. Consider the difference between a 6 year old and an infant. Ironically, even though this is the period of the most significant growth -more than in all the remaining years combined, it is the plane most often ignored by traditional education, where “real school” begins at 6 years old. But that is a topic for another discussion.

Understanding Dr. Montessori’s planes of development can help us to better grasp the necessary relationship between struggle and growth. The spiraling curve image in this post represents a magnified view of the intricacies occuring within the peaks and valleys she identified. Even during the periods of ascent, there will be setbacks, regression, stagnation and fluctuating effort. Likewise, children will continue to make great strides during the declines.

If we elevate our view of that spiral curve to consider the whole child and everything he or she is learning, the picture would reveal hundreds or thousands of individual spiraled lines all moving along the general upward sloping curve. Spirals might be long and elipitical or incredibly tight and tiny. Each backward loop is a moment of high internal effort, but also perhaps even confusion or low productivity. Each upward swing is a moment of success which tracks back directly to the backward loop. In this way, the child continually cycles through struggle, effort, and success.

In terms of the teacher’s role, there is a sweet spot somewhere within the ratio of struggle to success. Achieving it is not easy and requires a balanced teacher/child relationship and individualized instruction with each child in the room. This virtually defies the use of standardized assessment which typically uses a few data points by which to deem a child at grade level, ahead or behind. Instead of assigning work in bulk to the entire class and then helping those who need it, Montessori teachers work with each child to ensure we never assign work which they cannot do.

Again, struggling is good, but when you cross the fine line into unavoidable failure too many times, the mistakes become counter-productive or even detrimental to a child’s overall love of learning, to say nothing of his or her appreciation for the topic. Just think back into your own education and try to remember what it felt like to be staring at your homework as if it was the first time you had ever seen the concept. This experience is almost enough to turn a child away from an entire subject forever. Add the increased pressure of a child’s world in 2021 and it is not difficult to see why matching each child to the lesson is such an important idea.

How do parents stay in tune through all this spiraling? Can we simply check-in anywhere on that learning curve? Yes, you could. Tracking a vertical line down through all of these skills would represent a broad picture of the child during that brief moment in his or her life. However, what you learn about your child should not be considered too heavily as a prediction of the future or even an assessment of the past.

Observation is your best tool, but it works best when practiced intentionally over a period of time rather than haphazardly here and there. Regular observation will help you keep up with them. Rather than focusing upon a fixed point for assessment, or even a connected set of points, we should all view the timeline of learning itself as a flexible, continuous, sometimes meandering, infinitely faceted indicator of human thriving. That way, it might be easier to comfortably expect a wide and fluctuating range of development from failure to success. In turn, perhaps it becomes just as easy to appreciate the valleys as much as the peaks.